Improving test writing via a qualitative study

At work I often have side projects — things that aren’t exactly on the roadmap but that I think are worth doing and that leadership gives a blessing to. Sometimes it’s a proof-of-concept, sometimes it’s better described as “glue work” — work that helps us function better as a software development operation.

One of my latest has been thinking about how to improve our automated testing.

Kibana is historically super heavy on end-to-end browser-based testing (the team calls these “functional tests”) and it gets expensive. With the upcoming release of three distinct incarnations of Kibana,1 each with its own test suite, the problem has only grown.

Now, I can sympathize with our top-heavy testing pyramid. We’re heavy on UI in a way that a project like Elasticsearch definitely isn’t.

But, functional tests are also flaky, especially at scale. This is a bigger deal than we might be tempted to give it credit for. And, though indispensible as a high-fidelity validation engine, functional tests are just inefficient for fine-grained UI testing.

Kibana is a complex analytics platform with miles of UI views. But these views are composed of smaller user experiences, each of which can have many interaction permutations. It’s much more efficient and robust to test these small, complicated units in a more isolated environment.

So, I wondered, why do we write so many functional tests?

I asked this question at our engineering conference. I expressed surprise at how we test our application. I got the sense people just didn’t love writing Jest tests.

Later that year, I started interviewing my teammates and folks from our sister teams, using a few prepared prompts to get the discussion going:

- Compare/contrast your experiences writing unit and functional tests.

- What are your biggest points of friction when using Jest to test UI in Kibana? (I purposely avoided the term “unit test” since that implies a specific level of granularity.)

- What strategies have you found useful to increase the effectiveness or maintainability of your tests?

As I took notes from each interview, themes quickly emerged.

The first was a bit surprising and didn’t have anything to do with tech, but everything to do with people.

Nearly everyone I spoke with brought up the question I had asked months ago at the engineering conference. Many of them had been thinking about it since. This just underscored the longevity a discussion can have. It had really “greased the rails,” creating an organizational readiness for further knowledge and change.

On the technical side, folks pointed out that Kibana’s dependency injection system isn’t available during Jest tests, so it is often impossible to get ahold of key dependencies. This leads to the need for writing many mocks, a source of friction. This problem persists but I mention it here because, while general principles are important, to be most helpful, they need to be viewed in light of a particular organization or codebase.

Hence, the importance of the Kibana component in the second question:

What are your biggest points of friction when using Jest to test UI in Kibana?

But the theme I really started digging into was that Enzyme2 (our usual tool of choice to write Jest tests for UI) was just a bad developer experience.

Components under test in Enzyme often don’t act like they do in the browser without some serious coaxing. Usually, this is because Enzyme does a poor job of handling asynchronous behavior. I found that developers had all sorts of tricks to force their React components into the right state and they routinely sprinkled these hacks all over until the component started “working properly.”

After having to do so much just to get the UI to act like it really does in our application, it’s hard not to question the fidelity (and hence, the value) of the tests anyways. (My tech lead called these “glorified compilation checks” because that’s basically all they amount to.)

Enzyme also lacks the visual feedback of a browser test. When a browser test is failing, you can run the test and literally watch the test runner click through the app until something fails. Enzyme just tells you it couldn’t find a DOM element that matched your query. Good luck!

The cool thing about side projects is that they add a hook to your brain. When you see something relevant to your project as you’re going about your scheduled work, you notice it in a way you wouldn’t if you didn’t have an agenda.

I took my next large UI project as an opportunity to try out React Testing Library3 (RTL) and quickly found that it solved the fundamental DX and trust problems of Enzyme.

Async behavior is easy to handle in RTL. It provides great helpers very similar to those we use in our browser test runner. You no longer have to delve into React render cycles to understand why things are failing… if you know something is supposed to happen, just wait for it like you do in a functional test.

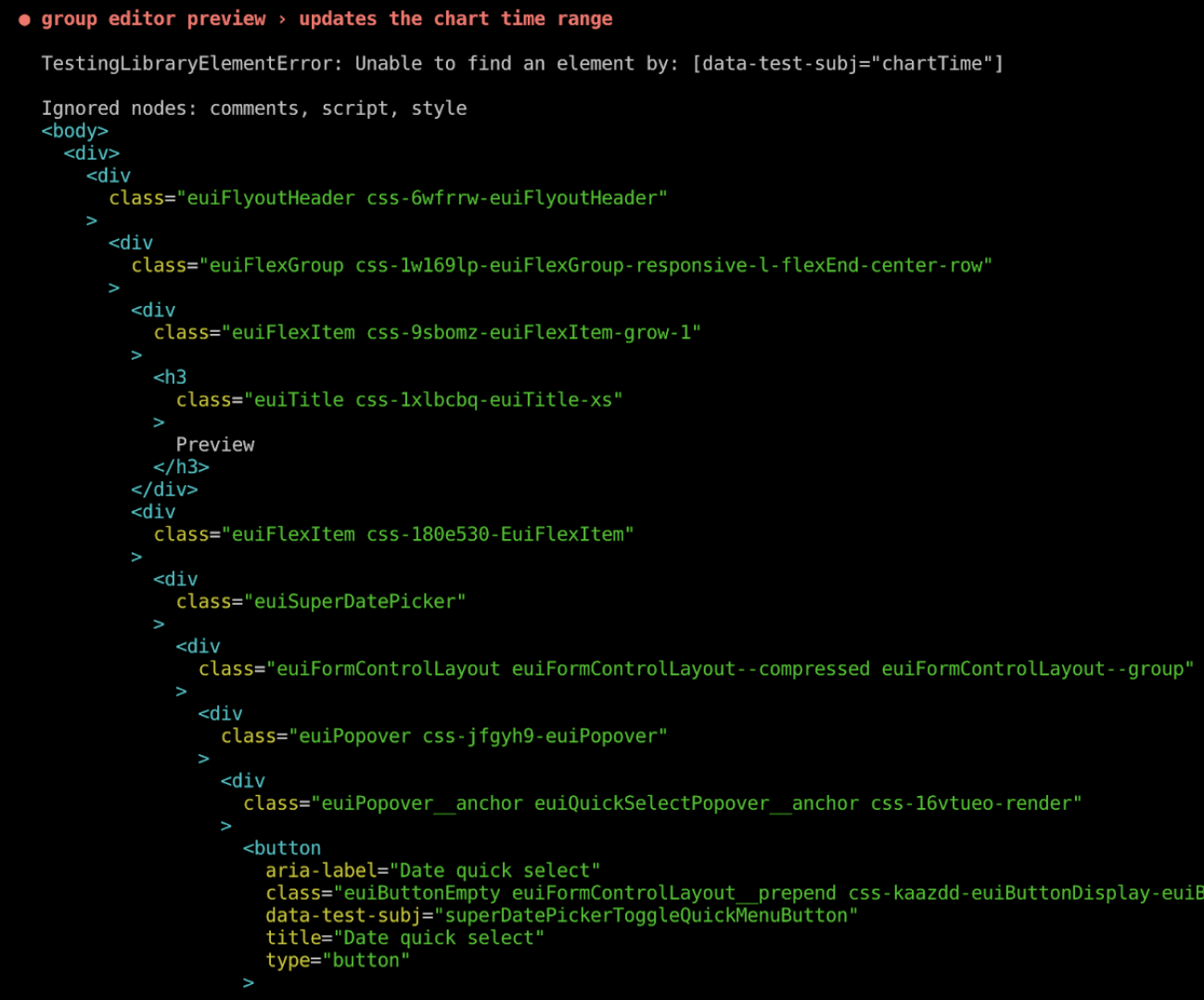

If the RTL test runner can’t find the element matching your query, it pretty-prints the whole DOM with helpful messages.

Visual feedback? Check!

What’s more is that RTL builds trust in the test by pushing tests to rely on DOM interactions instead of React APIs. This makes tests interact with the very same interface your customers do.5

I was wowed and I quickly wrote an RFC proposing we cease and desist from using Enzyme and we use RTL for all new Jest UI tests.

That kind of change proposal seems destined to succeed: concretely actionable, easily adoptable (no rewriting of existing tests), and proven out with a proof-of-concept. In addition, a few other developers on the team had already been experimenting with RTL and were ready to be advocates and teachers. The decision just needed to be formalized.

The team decided to accept the proposal. We had the willingness. We just needed the knowledge. So, I prepared a presentation to introduce everyone to the to the new framework.

Here’s the presentation I gave (built with Big).

Did it make a difference?

I haven’t gotten around to quantitative analysis of the number of this test vs. that one. Maybe I’ll update this post when I do.

But, qualitatively, I know it has made it easy to do the right thing: write less-expensive, higher-quality tests. In the months since the change, many of my teammates have told me how much better things are. One said, “I actually enjoy writing unit tests.”

This is the kind of change that incentivizes itself. As soon as people catch the vision, the change will be sustained and broad, perhaps even broader than the proposal.

We’ll be all the better for it.

Footnotes

- Part of the Elastic serverless products

- Enzyme website

- React Testing Library website

- See here for an overview of RTL’s async handling

- Read more about the philosophy behind confining tests to DOM assertions here